-

Agriculture

Agriculture

-

Health-Care

Health-Care

-

Environment

Environment

-

Construction-Real-Estate

Construction-Real-Estate

-

Tools-Hardware

Tools-Hardware

-

Home-Garden

Home-Garden

-

Furniture

Furniture

-

Luggage-Bags-Cases

Luggage-Bags-Cases

-

Medical-devices-Supplies

Medical-devices-Supplies

-

Gifts-Crafts

Gifts-Crafts

-

Sports-Entertainment

Sports-Entertainment

-

Food-Beverage

Food-Beverage

-

Vehicles-Transportation

Vehicles-Transportation

-

Power-Transmission

Power-Transmission

-

Material-Handling

Material-Handling

-

Renewable-Energy

Renewable-Energy

-

Safety

Safety

-

Testing-Instrument-Equipment

Testing-Instrument-Equipment

-

Construction-Building-Machinery

Construction-Building-Machinery

-

Pet-Supplies

Pet-Supplies

-

Personal-Care-Household-Cleaning

Personal-Care-Household-Cleaning

-

Vehicle-Accessories-Electronics-Tools

Vehicle-Accessories-Electronics-Tools

-

School-Office-Supplies

School-Office-Supplies

-

Packaging-Printing

Packaging-Printing

-

Mother-Kids-Toys

Mother-Kids-Toys

-

Business-Services

Business-Services

-

Commercial-Equipment-Machinery

Commercial-Equipment-Machinery

-

Apparel-Accessories

Apparel-Accessories

-

Security

Security

-

Shoes-Accessories

Shoes-Accessories

-

Vehicle-Parts-Accessories

Vehicle-Parts-Accessories

-

Jewelry-Eyewear-Watches-Accessories

Jewelry-Eyewear-Watches-Accessories

-

Lights-Lighting

Lights-Lighting

-

Fabric-Textile-Raw-Material

Fabric-Textile-Raw-Material

-

Fabrication-Services

Fabrication-Services

-

Industrial-Machinery

Industrial-Machinery

-

Consumer-Electronics

Consumer-Electronics

-

Electrical-Equipment-Supplies

Electrical-Equipment-Supplies

-

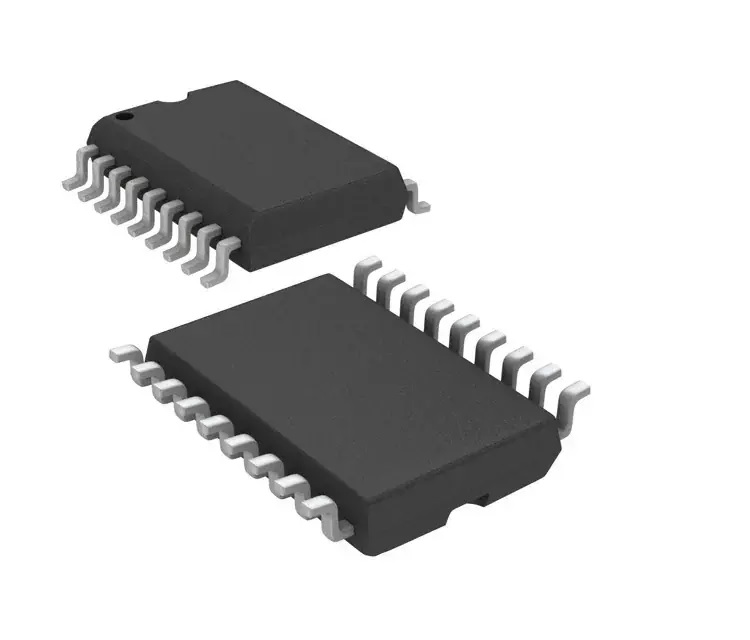

Electronic-Components-Accessories-Telecommunications

Electronic-Components-Accessories-Telecommunications

-

Home-Appliances

Home-Appliances

-

Beauty

Beauty

-

Chemicals

Chemicals

-

Rubber-Plastics

Rubber-Plastics

-

Metals-Alloys

Metals-Alloys

- Masonry Materials

- Curtain Walls & Accessories

- Earthwork Products

- Fireproofing Materials

- Heat Insulation Materials

- Plastic Building Materials

- Building Boards

- Soundproofing Materials

- Timber

- Waterproofing Materials

- Balustrades & Handrails

- Bathroom & Kitchen

- Flooring & Accessories

- Tiles & Accessories

- Door, Window & Accessories

- Fireplaces & Stoves

- Floor Heating Systems & Parts

- Stairs & Stair Parts

- Ceilings

- Elevators & Escalators

- Stone

- Countertops, Vanity Tops & Table Tops

- Mosaics

- Metal Building Materials

- Multifunctional Materials

- Ladders & Scaffoldings

- Mouldings

- Corner Guards

- Decorative Films

- Formwork

- Building & Industrial Glass

- Other Construction & Real Estate

- Wallpapers/Wall panels

- HVAC System & Parts

- Outdoor Facilities

- Prefabricated Buildings

- Festive & Party Supplies

- Bathroom Products

- Household Sundries

- Rain Gear

- Garden Supplies

- Household Cleaning Tools & Accessories

- Lighters & Smoking Accessories

- Home Storage & Organization

- Household Scales

- Smart Home Improvement

- Home Textiles

- Kitchenware

- Drinkware & Accessories

- Dinnerware, Coffee & Wine

- Home Decor

- Golf

- Fitness & Body Building

- Amusement Park Facilities

- Billiards, Board Game,Coin Operated Games

- Musical Instruments

- Outdoor Affordable Luxury Sports

- Camping & Hiking

- Fishing

- Sports Safety&Rehabilitation

- Ball Sports Equipments

- Water Sports

- Winter Sports

- Luxury Travel Equipments

- Sports Shoes, Bags & Accessories

- Cycling

- Other Sports & Entertainment Products

- Artificial Grass&Sports Flooring&Sports Court Equipment

- Scooters

- Food Ingredients

- Honey & Honey Products

- Snacks

- Nuts & Kernels

- Seafood

- Plant & Animal Oil

- Beverages

- Fruit & Vegetable Products

- Frog & Escargot

- Bean Products

- Egg Products

- Dairy Products

- Seasonings & Condiments

- Canned Food

- Instant Food

- Baked Goods

- Other Food & Beverage

- Meat & Poultry

- Confectionery

- Grain Products

- Feminie Care

- Hair Care & Styling

- Body Care

- Hands & Feet Care

- Hygiene Products

- Men's Grooming

- Laundry Cleaning Supplies

- Travel Size & Gift Sets

- Room Deodorizers

- Other Personal Care Products

- Pest Control Products

- Special Household Cleaning

- Floor Cleaning

- Kitchen & Bathroom Cleaning

- Oral Care

- Bath Supplies

- Yellow Pages

- Correction Supplies

- Office Binding Supplies

- Office Cutting Supplies

- Board Erasers

- Office Adhesives & Tapes

- Education Supplies

- Pencil Cases & Bags

- Notebooks & Writing Pads

- File Folder Accessories

- Calendars

- Writing Accessories

- Commercial Office Supplies

- Pencil Sharpeners

- Pens

- Letter Pad/Paper

- Paper Envelopes

- Desk Organizers

- Pencils

- Markers & Highlighters

- Filing Products

- Art Supplies

- Easels

- Badge Holder & Accessories

- Office Paper

- Printer Supplies

- Book Covers

- Other Office & School Supplies

- Stationery Set

- Boards

- Clipboards

- Stamps

- Drafting Supplies

- Stencils

- Electronic Dictionary

- Books

- Map

- Magazines

- Calculators

- Baby & Toddler Toys

- Educational Toys

- Classic Toys

- Dress Up & Pretend Play

- Toy Vehicle

- Stuffed Animals & Plush Toys

- Outdoor Toys & Structures

- Balloons & Accessories

- Baby Food

- Children's Clothing

- Baby Supplies & Products

- Maternity Clothes

- Kids Shoes

- Baby Care

- Novelty & Gag Toys

- Dolls & Accessories

- Puzzle & Games

- Blocks & Model Building Toys

- Toddler Clothing

- Baby Clothing

- Kids' Luggage & Bags

- Arts, Crafts & DIY Toys

- Action & Toy Figures

- Baby Appliances

- Hobbies & Models

- Remote Control Toys

- Promotional Toys

- Pregnancy & Maternity

- Hygiene Products

- Kid's Textile&Bedding

- Novelty & Special Use

- Toy Weapons

- Baby Gifts

- Baby Storage & Organization

- Auto Drive Systems

- ATV/UTV Parts & Accessories

- Marine Parts & Accessories

- Other Auto Parts

- Trailer Parts & Accessories

- Auto Transmission Systems

- Train Parts & Accessories

- Universal Parts

- Railway Parts & Accessories

- Auto Brake Systems

- Aviation Parts & Accessories

- Truck Parts & Accessories

- Auto Suspension Systems

- Auto Lighting Systems

- New Energy Vehicle Parts & Accessories

- Auto Steering Systems

- Wheels, Tires & Accessories

- Bus Parts & Accessories

- Auto Performance Parts

- Cooling System

- Go-Kart & Kart Racer Parts & Accessories

- Air Conditioning Systems

- Heavy Duty Vehicle Parts & Accessories

- Auto Electrical Systems

- Auto Body Systems

- Auto Engine Systems

- Container Parts & Accessories

- Motorcycle Parts & Accessories

- Refrigeration & Heat Exchange Equipment

- Machine Tool Equipment

- Food & Beverage Machinery

- Agricultural Machinery & Equipment

- Apparel & Textile Machinery

- Chemical Machinery

- Packaging Machines

- Paper Production Machinery

- Plastic & Rubber Processing Machinery

- Industrial Robots

- Electronic Products Machinery

- Metal & Metallurgy Machinery

- Woodworking Machinery

- Home Product Manufacturing Machinery

- Machinery Accessories

- Environmental Machinery

- Machinery Service

- Electrical Equipment Manufacturing Machinery

- Industrial Compressors & Parts

- Tobacco & Cigarette Machinery

- Production Line

- Used Industrial Machinery

- Electronics Production Machinery

- Other Machinery & Industrial Equipment

- Camera, Photo & Accessories

- Portable Audio, Video & Accessories

- Television, Home Audio, Video & Accessories

- Video Games & Accessories

- Mobile Phone & Accessories

- Electronic Publications

- Earphone & Headphone & Accessories

- Speakers & Accessories

- Smart Electronics

- TV Receivers & Accessories

- Mobile Phone & Computer Repair Parts

- Chargers, Batteries & Power Supplies

- Used Electronics

- VR, AR, MR Hardware & Software

- Projectors & Presentation Equipments

- Other Consumer Electronics

- Cables & Commonly Used Accessories

- Computer Hardware & Software

- Displays, Signage and Optoelectronics

- Discrete Semiconductors

- Wireless & IoT Module and Products

- Telecommunications

- Connectors, Terminals & Accessories

- Development Boards, Electronic Modules and Kits

- Circuit Protection

- Sensors

- Isolators

- Audio Components and Products

- Integrated Circuits

- Power Supplies

- Relays

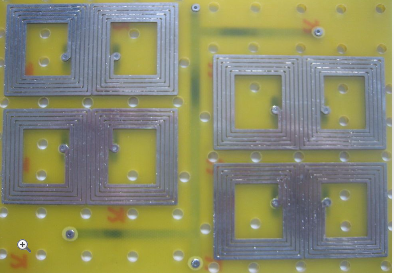

- RF, Microwave and RFID

- Electronic Accessories & Supplies

- Passive Components

- PCB & PCBA

- Air Quality Appliances

- Home Appliance Parts

- Heating & Cooling Appliances

- Small Kitchen Appliances

- Laundry Appliances

- Water Heaters

- Water Treatment Appliances

- Refrigerators & Freezers

- Personal Care & Beauty Appliances

- Major Kitchen Appliances

- Cleaning Appliances

- Second-hand Appliances

- Smart Home Appliances

- Other Home Appliances

- Energy Chemicals

- Inorganic Chemicals

- Basic Organic Chemicals

- Agrochemicals

- Admixture & Additives

- Catalysts & Chemical Auxiliary Agents

- Pigments & Dyestuff

- Coating & Paint

- Daily Chemicals

- Polymer

- Organic Intermediate

- Adhesives & Sealants

- Chemical Waste

- Biological Chemical Products

- Surface Treatment Chemicals

- Painting & Coating

- Chemical Reagents

- Flavor & Fragrance

- Non-Explosive Demolition Agents

- Other Chemicals

- Custom Chemical Services

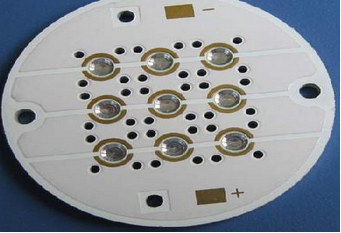

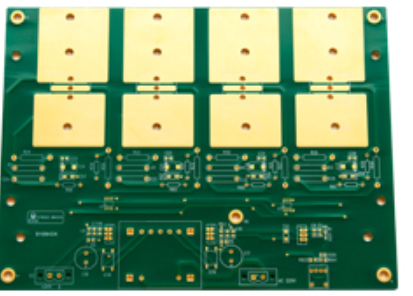

Heavy Copper PCBs Engineered For Maximum Reliability In Power Electronics With Thick Copper Layers Ensuring Long Term Performance

In the rapidly evolving world of power electronics, where efficiency, durability, and thermal management are paramount, a specialized class of printed circuit boards (PCBs) has emerged as a critical enabler of innovation and reliability. These are Heavy Copper PCBs, engineered specifically to handle high currents, dissipate significant heat, and withstand harsh operational environments. Unlike standard PCBs with copper weights typically around 1 oz/ft² (35 µm), heavy copper PCBs feature copper layers that can range from 3 oz/ft² to an extraordinary 20 oz/ft² or more. This fundamental design choice transforms the PCB from a simple interconnect platform into a robust, integral component of the power system itself. The promise of "Maximum Reliability" and "Long-Term Performance" is not merely a marketing claim but a direct result of this engineered thickness, addressing the core challenges that plague conventional boards in high-power applications such as electric vehicle powertrains, industrial motor drives, renewable energy inverters, and aerospace power distribution. As demands for power density and operational lifespan increase, understanding the engineering behind these thick-copper workhorses becomes essential for anyone designing the next generation of electronic systems.

The Engineering Foundation: Copper Weight and Its Direct Impact

The defining characteristic of a Heavy Copper PCB is, unsurprisingly, the thickness of its copper traces and planes. This is quantified as copper weight, expressed in ounces per square foot (oz/ft²), representing the weight of copper spread evenly over a one-square-foot area. For context, 1 oz/ft² copper translates to a thickness of approximately 1.4 mils (35 micrometers). A heavy copper board starts at 3 oz/ft² and can extend to 10 oz, 15 oz, or even 20 oz for extreme applications. This substantial increase in cross-sectional area is governed by the fundamental principle of electrical conductivity: resistance is inversely proportional to the cross-sectional area of the conductor.

By dramatically increasing the copper's cross-section, the board's current-carrying capacity, or ampacity, is significantly enhanced. This allows the PCB to route high currents without the risk of trace overheating, voltage drop, or catastrophic failure due to fusing. Furthermore, the thicker copper provides a much lower impedance path, which is crucial for minimizing power losses (I²R losses) in high-current applications. Every watt saved from resistive heating translates directly into higher system efficiency and less thermal stress on surrounding components. This foundational engineering decision is the first and most critical step in building a PCB capable of reliable, long-term performance in power-dense environments.

Thermal Management: The Heart of Reliability

In power electronics, heat is the primary adversary of reliability. Excessive temperatures degrade component performance, accelerate chemical reactions leading to failure, and can cause delamination of the PCB itself. Heavy Copper PCBs excel as integrated thermal management systems. The thick copper layers act as excellent heat spreaders, conducting thermal energy away from hot spots such as power MOSFETs, IGBTs, or diodes, and distributing it across a larger area of the board.

This inherent heat-spreading capability reduces the peak operating temperature of critical components, directly extending their operational lifespan according to Arrhenius' law, which states that failure rates often double with every 10°C increase in temperature. Moreover, the thick copper facilitates a more efficient connection to external heatsinks. Thermal vias—plated holes filled or coated with copper—can be used in conjunction with heavy copper planes to create a low-thermal-resistance path from a component's thermal pad, through the board, and into a chassis or heatsink. This integrated approach often eliminates the need for bulky and costly secondary thermal interfaces or insulated metal substrates in many applications, simplifying assembly and reducing points of potential thermal failure over time.

Mechanical Robustness and Structural Integrity

Long-term performance is not solely about electrical and thermal characteristics; it also demands exceptional mechanical strength. The processes used to manufacture Heavy Copper PCBs, such as differential etching and specialized plating, result in robust internal structures. The thick copper planes add substantial rigidity to the overall board assembly, making it more resistant to bending, vibration, and mechanical shock—common challenges in automotive, industrial, and aerospace settings.

This structural benefit is particularly evident in through-hole applications. Plated through-holes (PTHs) that carry high current or are subject to repeated thermal cycling are common failure points. In a heavy copper board, the barrel of the via is plated with a correspondingly thick layer of copper. This reinforces the via, providing superior resistance to thermal stress and preventing barrel cracking, a typical failure mode that can interrupt current paths after thousands of power cycles. The enhanced adhesion of the thick copper to the substrate material also improves the board's resistance to delamination, especially during the extreme temperatures encountered in lead-free soldering processes.

Design Advantages and Miniaturization Potential

While heavy copper boards are physically robust, they also enable smarter and more compact designs. The high current-carrying capacity of a single thick trace allows designers to reduce the number of parallel traces or layers previously needed to distribute current. This can simplify the layout, improve reliability by reducing interconnection complexity, and potentially reduce the layer count of a multilayer board.

Furthermore, this capability enables significant miniaturization. A designer can achieve the same ampacity in a much narrower trace width with heavy copper compared to standard copper. This allows for the creation of more power-dense modules where space is at a premium, such as in onboard chargers for electric vehicles or server power supplies. The ability to integrate high-power paths, control circuitry, and even planar magnetic elements (like transformer windings) onto a single heavy copper substrate leads to a more integrated, reliable, and manufacturable final product. This design integration reduces the number of discrete components and interconnects, which are frequent sources of field failure, thereby bolstering the system's long-term reliability.

Manufacturing Considerations and Long-Term Value

The fabrication of Heavy Copper PCBs is a specialized process that demands expertise. Techniques like step plating, where different areas of the board receive different copper thicknesses, or controlled-depth milling, allow for the creation of boards that combine fine-pitch control logic circuitry with high-current bus bars on the same substrate. While the manufacturing cost per unit area is higher than for standard PCBs, the total system cost and long-term value are often superior.

This value is realized through enhanced field reliability, reduced warranty claims, and lower lifetime maintenance costs. A well-engineered heavy copper PCB is an investment in preventing catastrophic failures that can lead to costly downtime, especially in critical industrial or infrastructure applications. Its ability to endure repeated thermal cycling, high inrush currents, and mechanical vibration without degradation ensures that the power electronic system performs as intended over its entire designed service life. In essence, the upfront engineering and manufacturing investment pays dividends through unwavering performance and durability, truly ensuring the "long-term performance" promised in its design philosophy.

REPORT