-

Agriculture

Agriculture

-

Health-Care

Health-Care

-

Environment

Environment

-

Construction-Real-Estate

Construction-Real-Estate

-

Tools-Hardware

Tools-Hardware

-

Home-Garden

Home-Garden

-

Furniture

Furniture

-

Luggage-Bags-Cases

Luggage-Bags-Cases

-

Medical-devices-Supplies

Medical-devices-Supplies

-

Gifts-Crafts

Gifts-Crafts

-

Sports-Entertainment

Sports-Entertainment

-

Food-Beverage

Food-Beverage

-

Vehicles-Transportation

Vehicles-Transportation

-

Power-Transmission

Power-Transmission

-

Material-Handling

Material-Handling

-

Renewable-Energy

Renewable-Energy

-

Safety

Safety

-

Testing-Instrument-Equipment

Testing-Instrument-Equipment

-

Construction-Building-Machinery

Construction-Building-Machinery

-

Pet-Supplies

Pet-Supplies

-

Personal-Care-Household-Cleaning

Personal-Care-Household-Cleaning

-

Vehicle-Accessories-Electronics-Tools

Vehicle-Accessories-Electronics-Tools

-

School-Office-Supplies

School-Office-Supplies

-

Packaging-Printing

Packaging-Printing

-

Mother-Kids-Toys

Mother-Kids-Toys

-

Business-Services

Business-Services

-

Commercial-Equipment-Machinery

Commercial-Equipment-Machinery

-

Apparel-Accessories

Apparel-Accessories

-

Security

Security

-

Shoes-Accessories

Shoes-Accessories

-

Vehicle-Parts-Accessories

Vehicle-Parts-Accessories

-

Jewelry-Eyewear-Watches-Accessories

Jewelry-Eyewear-Watches-Accessories

-

Lights-Lighting

Lights-Lighting

-

Fabric-Textile-Raw-Material

Fabric-Textile-Raw-Material

-

Fabrication-Services

Fabrication-Services

-

Industrial-Machinery

Industrial-Machinery

-

Consumer-Electronics

Consumer-Electronics

-

Electrical-Equipment-Supplies

Electrical-Equipment-Supplies

-

Electronic-Components-Accessories-Telecommunications

Electronic-Components-Accessories-Telecommunications

-

Home-Appliances

Home-Appliances

-

Beauty

Beauty

-

Chemicals

Chemicals

-

Rubber-Plastics

Rubber-Plastics

-

Metals-Alloys

Metals-Alloys

- Masonry Materials

- Curtain Walls & Accessories

- Earthwork Products

- Fireproofing Materials

- Heat Insulation Materials

- Plastic Building Materials

- Building Boards

- Soundproofing Materials

- Timber

- Waterproofing Materials

- Balustrades & Handrails

- Bathroom & Kitchen

- Flooring & Accessories

- Tiles & Accessories

- Door, Window & Accessories

- Fireplaces & Stoves

- Floor Heating Systems & Parts

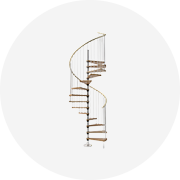

- Stairs & Stair Parts

- Ceilings

- Elevators & Escalators

- Stone

- Countertops, Vanity Tops & Table Tops

- Mosaics

- Metal Building Materials

- Multifunctional Materials

- Ladders & Scaffoldings

- Mouldings

- Corner Guards

- Decorative Films

- Formwork

- Building & Industrial Glass

- Other Construction & Real Estate

- Wallpapers/Wall panels

- HVAC System & Parts

- Outdoor Facilities

- Prefabricated Buildings

- Festive & Party Supplies

- Bathroom Products

- Household Sundries

- Rain Gear

- Garden Supplies

- Household Cleaning Tools & Accessories

- Lighters & Smoking Accessories

- Home Storage & Organization

- Household Scales

- Smart Home Improvement

- Home Textiles

- Kitchenware

- Drinkware & Accessories

- Dinnerware, Coffee & Wine

- Home Decor

- Golf

- Fitness & Body Building

- Amusement Park Facilities

- Billiards, Board Game,Coin Operated Games

- Musical Instruments

- Outdoor Affordable Luxury Sports

- Camping & Hiking

- Fishing

- Sports Safety&Rehabilitation

- Ball Sports Equipments

- Water Sports

- Winter Sports

- Luxury Travel Equipments

- Sports Shoes, Bags & Accessories

- Cycling

- Other Sports & Entertainment Products

- Artificial Grass&Sports Flooring&Sports Court Equipment

- Scooters

- Food Ingredients

- Honey & Honey Products

- Snacks

- Nuts & Kernels

- Seafood

- Plant & Animal Oil

- Beverages

- Fruit & Vegetable Products

- Frog & Escargot

- Bean Products

- Egg Products

- Dairy Products

- Seasonings & Condiments

- Canned Food

- Instant Food

- Baked Goods

- Other Food & Beverage

- Meat & Poultry

- Confectionery

- Grain Products

- Feminie Care

- Hair Care & Styling

- Body Care

- Hands & Feet Care

- Hygiene Products

- Men's Grooming

- Laundry Cleaning Supplies

- Travel Size & Gift Sets

- Room Deodorizers

- Other Personal Care Products

- Pest Control Products

- Special Household Cleaning

- Floor Cleaning

- Kitchen & Bathroom Cleaning

- Oral Care

- Bath Supplies

- Yellow Pages

- Correction Supplies

- Office Binding Supplies

- Office Cutting Supplies

- Board Erasers

- Office Adhesives & Tapes

- Education Supplies

- Pencil Cases & Bags

- Notebooks & Writing Pads

- File Folder Accessories

- Calendars

- Writing Accessories

- Commercial Office Supplies

- Pencil Sharpeners

- Pens

- Letter Pad/Paper

- Paper Envelopes

- Desk Organizers

- Pencils

- Markers & Highlighters

- Filing Products

- Art Supplies

- Easels

- Badge Holder & Accessories

- Office Paper

- Printer Supplies

- Book Covers

- Other Office & School Supplies

- Stationery Set

- Boards

- Clipboards

- Stamps

- Drafting Supplies

- Stencils

- Electronic Dictionary

- Books

- Map

- Magazines

- Calculators

- Baby & Toddler Toys

- Educational Toys

- Classic Toys

- Dress Up & Pretend Play

- Toy Vehicle

- Stuffed Animals & Plush Toys

- Outdoor Toys & Structures

- Balloons & Accessories

- Baby Food

- Children's Clothing

- Baby Supplies & Products

- Maternity Clothes

- Kids Shoes

- Baby Care

- Novelty & Gag Toys

- Dolls & Accessories

- Puzzle & Games

- Blocks & Model Building Toys

- Toddler Clothing

- Baby Clothing

- Kids' Luggage & Bags

- Arts, Crafts & DIY Toys

- Action & Toy Figures

- Baby Appliances

- Hobbies & Models

- Remote Control Toys

- Promotional Toys

- Pregnancy & Maternity

- Hygiene Products

- Kid's Textile&Bedding

- Novelty & Special Use

- Toy Weapons

- Baby Gifts

- Baby Storage & Organization

- Auto Drive Systems

- ATV/UTV Parts & Accessories

- Marine Parts & Accessories

- Other Auto Parts

- Trailer Parts & Accessories

- Auto Transmission Systems

- Train Parts & Accessories

- Universal Parts

- Railway Parts & Accessories

- Auto Brake Systems

- Aviation Parts & Accessories

- Truck Parts & Accessories

- Auto Suspension Systems

- Auto Lighting Systems

- New Energy Vehicle Parts & Accessories

- Auto Steering Systems

- Wheels, Tires & Accessories

- Bus Parts & Accessories

- Auto Performance Parts

- Cooling System

- Go-Kart & Kart Racer Parts & Accessories

- Air Conditioning Systems

- Heavy Duty Vehicle Parts & Accessories

- Auto Electrical Systems

- Auto Body Systems

- Auto Engine Systems

- Container Parts & Accessories

- Motorcycle Parts & Accessories

- Refrigeration & Heat Exchange Equipment

- Machine Tool Equipment

- Food & Beverage Machinery

- Agricultural Machinery & Equipment

- Apparel & Textile Machinery

- Chemical Machinery

- Packaging Machines

- Paper Production Machinery

- Plastic & Rubber Processing Machinery

- Industrial Robots

- Electronic Products Machinery

- Metal & Metallurgy Machinery

- Woodworking Machinery

- Home Product Manufacturing Machinery

- Machinery Accessories

- Environmental Machinery

- Machinery Service

- Electrical Equipment Manufacturing Machinery

- Industrial Compressors & Parts

- Tobacco & Cigarette Machinery

- Production Line

- Used Industrial Machinery

- Electronics Production Machinery

- Other Machinery & Industrial Equipment

- Camera, Photo & Accessories

- Portable Audio, Video & Accessories

- Television, Home Audio, Video & Accessories

- Video Games & Accessories

- Mobile Phone & Accessories

- Electronic Publications

- Earphone & Headphone & Accessories

- Speakers & Accessories

- Smart Electronics

- TV Receivers & Accessories

- Mobile Phone & Computer Repair Parts

- Chargers, Batteries & Power Supplies

- Used Electronics

- VR, AR, MR Hardware & Software

- Projectors & Presentation Equipments

- Other Consumer Electronics

- Cables & Commonly Used Accessories

- Computer Hardware & Software

- Displays, Signage and Optoelectronics

- Discrete Semiconductors

- Wireless & IoT Module and Products

- Telecommunications

- Connectors, Terminals & Accessories

- Development Boards, Electronic Modules and Kits

- Circuit Protection

- Sensors

- Isolators

- Audio Components and Products

- Integrated Circuits

- Power Supplies

- Relays

- RF, Microwave and RFID

- Electronic Accessories & Supplies

- Passive Components

- PCB & PCBA

- Air Quality Appliances

- Home Appliance Parts

- Heating & Cooling Appliances

- Small Kitchen Appliances

- Laundry Appliances

- Water Heaters

- Water Treatment Appliances

- Refrigerators & Freezers

- Personal Care & Beauty Appliances

- Major Kitchen Appliances

- Cleaning Appliances

- Second-hand Appliances

- Smart Home Appliances

- Other Home Appliances

- Energy Chemicals

- Inorganic Chemicals

- Basic Organic Chemicals

- Agrochemicals

- Admixture & Additives

- Catalysts & Chemical Auxiliary Agents

- Pigments & Dyestuff

- Coating & Paint

- Daily Chemicals

- Polymer

- Organic Intermediate

- Adhesives & Sealants

- Chemical Waste

- Biological Chemical Products

- Surface Treatment Chemicals

- Painting & Coating

- Chemical Reagents

- Flavor & Fragrance

- Non-Explosive Demolition Agents

- Other Chemicals

- Custom Chemical Services

Overflowing with souvenirs and treasures the overstuffed suitcase strains against its zippers barely containing the memories collected from a year abroad

Imagine standing before a suitcase so full that its fabric bulges at the seams, its zippers holding on for dear life. This is not merely a piece of luggage; it is a tangible archive, a physical testament to a year lived in a foreign land. Overflowing with souvenirs and treasures, the overstuffed suitcase strains against its zippers, barely containing the memories collected from a year abroad. This single, straining suitcase symbolizes the profound challenge every returning traveler faces: how to pack a transformative life experience into a finite, rectangular box. It represents the culmination of countless moments—the thrill of discovery, the pangs of homesickness, the joy of new friendships, and the quiet self-reflection—all now compressed, waiting to be unpacked in more ways than one. The journey home, it seems, begins with this first, stubborn zipper.

The Tangible Cargo: Objects as Memory Vessels

Every item crammed into the suitcase’s depths serves as a key to a specific memory. The crumpled museum ticket stub is not just paper; it is a portal back to a hushed gallery where a masterpiece took your breath away. The slightly chipped ceramic mug, carefully swaddled in a sweater, evokes the cozy mornings spent in a local café, watching a new city wake up. These are not random trinkets; they are carefully chosen relics. Each was selected after much deliberation in a market stall or a quiet shop, deemed worthy of representing a slice of life abroad.

The physicality of these objects is crucial. Their weight, texture, and even their slight imperfections—a scratch on a wooden figurine, the faded label on a spice jar—add layers of authenticity to the memories they hold. They are anchors. In the weeks and months after returning, when the vividness of the experience begins to soften at the edges, holding that peculiar coin or smelling the scent lingering on a woven scarf can instantly transport you back. The suitcase, therefore, is a chest of sensory triggers, each object a deliberate attempt to bottle a feeling, a place, or a person.

Yet, their collective mass creates a dilemma. The logical mind knows that the memory resides within, not within the object itself. But the heart argues differently. To discard even the most mundane item—a transit pass, a restaurant napkin—feels like discarding a piece of the journey. The overstuffed state of the suitcase is a physical manifestation of this emotional conflict, a battle between practicality and sentiment where sentiment, quite clearly, has won a resounding victory.

The Intangible Weight: Memories That Defy Packaging

For all its bulging contents, the suitcase’s greatest burden is invisible. It carries the echo of conversations in a newly familiar language, the taste of unfamiliar foods that became comfort meals, and the feeling of navigating a labyrinthine old town until it felt like home. It holds the memory of the first successful joke told in a foreign tongue, the solidarity found with other travelers, and the profound loneliness that sometimes descended on a rainy Sunday. These are the treasures that no zipper can contain.

This intangible cargo is what truly strains the seams of the traveler’s identity. The year abroad has subtly—or perhaps not so subtly—reshaped perspectives, challenged long-held beliefs, and instilled new rhythms of living. The person who packed the suitcase a year ago is not the same person trying to close it now. Inside are the quiet confidence gained from solving countless daily puzzles, the expanded worldview forged from witnessing different ways of life, and the bittersweet understanding of what \"home\" really means.

Unpacking this intangible weight is the real work that begins upon return. It involves integrating the person you became abroad with the life you left behind. It means finding ways to express experiences for which your old vocabulary feels inadequate. The suitcase, sitting in the corner of a familiar room, becomes a silent symbol of this internal integration process, a reminder of a world that now exists simultaneously out there and deep within.

The Metaphor of Transition: Between Two Worlds

The straining suitcase is a perfect metaphor for the liminal space the traveler inhabits at the journey’s end. It is caught between two worlds: the adventure that has concluded and the familiar life that is about to resume. The physical pressure on the zippers mirrors the psychological pressure of transition. There is a tension between the desire to hold onto every detail of the past year and the necessity to reintegrate into a routine that may now feel strangely constricting.

This state of \"in-between\" is fraught with contradiction. There is excitement to share stories with loved ones, coupled with the sinking realization that some experiences are fundamentally unshareable. There is relief in returning to comforts, tinged with a restless nostalgia for the vibrant uncertainty of life abroad. The suitcase, neither fully packed nor fully unpacked, embodies this suspended animation. It is a capsule of a past life that must somehow be opened into a present one.

Ultimately, the act of finally opening the suitcase and dispersing its contents is a ritual of synthesis. It is not an end, but a beginning. The souvenirs find new places on shelves, the clothes are washed, carrying the scents of a different detergent. Each item, as it is put away, helps to weave the threads of the abroad experience into the fabric of everyday life back home. The suitcase itself, once emptied, may be stored away, but its impression—the memory of its impossible fullness—remains, a testament to a year that was, quite literally, too big to contain.

REPORT