-

Agriculture

Agriculture

-

Health-Care

Health-Care

-

Environment

Environment

-

Construction-Real-Estate

Construction-Real-Estate

-

Tools-Hardware

Tools-Hardware

-

Home-Garden

Home-Garden

-

Furniture

Furniture

-

Luggage-Bags-Cases

Luggage-Bags-Cases

-

Medical-devices-Supplies

Medical-devices-Supplies

-

Gifts-Crafts

Gifts-Crafts

-

Sports-Entertainment

Sports-Entertainment

-

Food-Beverage

Food-Beverage

-

Vehicles-Transportation

Vehicles-Transportation

-

Power-Transmission

Power-Transmission

-

Material-Handling

Material-Handling

-

Renewable-Energy

Renewable-Energy

-

Safety

Safety

-

Testing-Instrument-Equipment

Testing-Instrument-Equipment

-

Construction-Building-Machinery

Construction-Building-Machinery

-

Pet-Supplies

Pet-Supplies

-

Personal-Care-Household-Cleaning

Personal-Care-Household-Cleaning

-

Vehicle-Accessories-Electronics-Tools

Vehicle-Accessories-Electronics-Tools

-

School-Office-Supplies

School-Office-Supplies

-

Packaging-Printing

Packaging-Printing

-

Mother-Kids-Toys

Mother-Kids-Toys

-

Business-Services

Business-Services

-

Commercial-Equipment-Machinery

Commercial-Equipment-Machinery

-

Apparel-Accessories

Apparel-Accessories

-

Security

Security

-

Shoes-Accessories

Shoes-Accessories

-

Vehicle-Parts-Accessories

Vehicle-Parts-Accessories

-

Jewelry-Eyewear-Watches-Accessories

Jewelry-Eyewear-Watches-Accessories

-

Lights-Lighting

Lights-Lighting

-

Fabric-Textile-Raw-Material

Fabric-Textile-Raw-Material

-

Fabrication-Services

Fabrication-Services

-

Industrial-Machinery

Industrial-Machinery

-

Consumer-Electronics

Consumer-Electronics

-

Electrical-Equipment-Supplies

Electrical-Equipment-Supplies

-

Electronic-Components-Accessories-Telecommunications

Electronic-Components-Accessories-Telecommunications

-

Home-Appliances

Home-Appliances

-

Beauty

Beauty

-

Chemicals

Chemicals

-

Rubber-Plastics

Rubber-Plastics

-

Metals-Alloys

Metals-Alloys

- Masonry Materials

- Curtain Walls & Accessories

- Earthwork Products

- Fireproofing Materials

- Heat Insulation Materials

- Plastic Building Materials

- Building Boards

- Soundproofing Materials

- Timber

- Waterproofing Materials

- Balustrades & Handrails

- Bathroom & Kitchen

- Flooring & Accessories

- Tiles & Accessories

- Door, Window & Accessories

- Fireplaces & Stoves

- Floor Heating Systems & Parts

- Stairs & Stair Parts

- Ceilings

- Elevators & Escalators

- Stone

- Countertops, Vanity Tops & Table Tops

- Mosaics

- Metal Building Materials

- Multifunctional Materials

- Ladders & Scaffoldings

- Mouldings

- Corner Guards

- Decorative Films

- Formwork

- Building & Industrial Glass

- Other Construction & Real Estate

- Wallpapers/Wall panels

- HVAC System & Parts

- Outdoor Facilities

- Prefabricated Buildings

- Festive & Party Supplies

- Bathroom Products

- Household Sundries

- Rain Gear

- Garden Supplies

- Household Cleaning Tools & Accessories

- Lighters & Smoking Accessories

- Home Storage & Organization

- Household Scales

- Smart Home Improvement

- Home Textiles

- Kitchenware

- Drinkware & Accessories

- Dinnerware, Coffee & Wine

- Home Decor

- Golf

- Fitness & Body Building

- Amusement Park Facilities

- Billiards, Board Game,Coin Operated Games

- Musical Instruments

- Outdoor Affordable Luxury Sports

- Camping & Hiking

- Fishing

- Sports Safety&Rehabilitation

- Ball Sports Equipments

- Water Sports

- Winter Sports

- Luxury Travel Equipments

- Sports Shoes, Bags & Accessories

- Cycling

- Other Sports & Entertainment Products

- Artificial Grass&Sports Flooring&Sports Court Equipment

- Scooters

- Food Ingredients

- Honey & Honey Products

- Snacks

- Nuts & Kernels

- Seafood

- Plant & Animal Oil

- Beverages

- Fruit & Vegetable Products

- Frog & Escargot

- Bean Products

- Egg Products

- Dairy Products

- Seasonings & Condiments

- Canned Food

- Instant Food

- Baked Goods

- Other Food & Beverage

- Meat & Poultry

- Confectionery

- Grain Products

- Feminie Care

- Hair Care & Styling

- Body Care

- Hands & Feet Care

- Hygiene Products

- Men's Grooming

- Laundry Cleaning Supplies

- Travel Size & Gift Sets

- Room Deodorizers

- Other Personal Care Products

- Pest Control Products

- Special Household Cleaning

- Floor Cleaning

- Kitchen & Bathroom Cleaning

- Oral Care

- Bath Supplies

- Yellow Pages

- Correction Supplies

- Office Binding Supplies

- Office Cutting Supplies

- Board Erasers

- Office Adhesives & Tapes

- Education Supplies

- Pencil Cases & Bags

- Notebooks & Writing Pads

- File Folder Accessories

- Calendars

- Writing Accessories

- Commercial Office Supplies

- Pencil Sharpeners

- Pens

- Letter Pad/Paper

- Paper Envelopes

- Desk Organizers

- Pencils

- Markers & Highlighters

- Filing Products

- Art Supplies

- Easels

- Badge Holder & Accessories

- Office Paper

- Printer Supplies

- Book Covers

- Other Office & School Supplies

- Stationery Set

- Boards

- Clipboards

- Stamps

- Drafting Supplies

- Stencils

- Electronic Dictionary

- Books

- Map

- Magazines

- Calculators

- Baby & Toddler Toys

- Educational Toys

- Classic Toys

- Dress Up & Pretend Play

- Toy Vehicle

- Stuffed Animals & Plush Toys

- Outdoor Toys & Structures

- Balloons & Accessories

- Baby Food

- Children's Clothing

- Baby Supplies & Products

- Maternity Clothes

- Kids Shoes

- Baby Care

- Novelty & Gag Toys

- Dolls & Accessories

- Puzzle & Games

- Blocks & Model Building Toys

- Toddler Clothing

- Baby Clothing

- Kids' Luggage & Bags

- Arts, Crafts & DIY Toys

- Action & Toy Figures

- Baby Appliances

- Hobbies & Models

- Remote Control Toys

- Promotional Toys

- Pregnancy & Maternity

- Hygiene Products

- Kid's Textile&Bedding

- Novelty & Special Use

- Toy Weapons

- Baby Gifts

- Baby Storage & Organization

- Auto Drive Systems

- ATV/UTV Parts & Accessories

- Marine Parts & Accessories

- Other Auto Parts

- Trailer Parts & Accessories

- Auto Transmission Systems

- Train Parts & Accessories

- Universal Parts

- Railway Parts & Accessories

- Auto Brake Systems

- Aviation Parts & Accessories

- Truck Parts & Accessories

- Auto Suspension Systems

- Auto Lighting Systems

- New Energy Vehicle Parts & Accessories

- Auto Steering Systems

- Wheels, Tires & Accessories

- Bus Parts & Accessories

- Auto Performance Parts

- Cooling System

- Go-Kart & Kart Racer Parts & Accessories

- Air Conditioning Systems

- Heavy Duty Vehicle Parts & Accessories

- Auto Electrical Systems

- Auto Body Systems

- Auto Engine Systems

- Container Parts & Accessories

- Motorcycle Parts & Accessories

- Refrigeration & Heat Exchange Equipment

- Machine Tool Equipment

- Food & Beverage Machinery

- Agricultural Machinery & Equipment

- Apparel & Textile Machinery

- Chemical Machinery

- Packaging Machines

- Paper Production Machinery

- Plastic & Rubber Processing Machinery

- Industrial Robots

- Electronic Products Machinery

- Metal & Metallurgy Machinery

- Woodworking Machinery

- Home Product Manufacturing Machinery

- Machinery Accessories

- Environmental Machinery

- Machinery Service

- Electrical Equipment Manufacturing Machinery

- Industrial Compressors & Parts

- Tobacco & Cigarette Machinery

- Production Line

- Used Industrial Machinery

- Electronics Production Machinery

- Other Machinery & Industrial Equipment

- Camera, Photo & Accessories

- Portable Audio, Video & Accessories

- Television, Home Audio, Video & Accessories

- Video Games & Accessories

- Mobile Phone & Accessories

- Electronic Publications

- Earphone & Headphone & Accessories

- Speakers & Accessories

- Smart Electronics

- TV Receivers & Accessories

- Mobile Phone & Computer Repair Parts

- Chargers, Batteries & Power Supplies

- Used Electronics

- VR, AR, MR Hardware & Software

- Projectors & Presentation Equipments

- Other Consumer Electronics

- Cables & Commonly Used Accessories

- Computer Hardware & Software

- Displays, Signage and Optoelectronics

- Discrete Semiconductors

- Wireless & IoT Module and Products

- Telecommunications

- Connectors, Terminals & Accessories

- Development Boards, Electronic Modules and Kits

- Circuit Protection

- Sensors

- Isolators

- Audio Components and Products

- Integrated Circuits

- Power Supplies

- Relays

- RF, Microwave and RFID

- Electronic Accessories & Supplies

- Passive Components

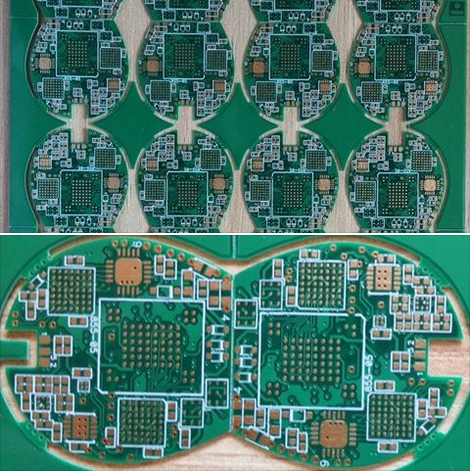

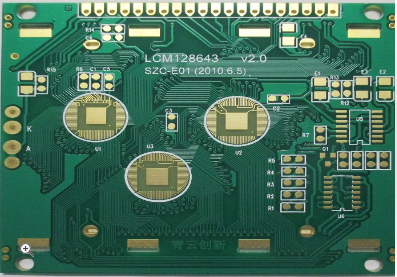

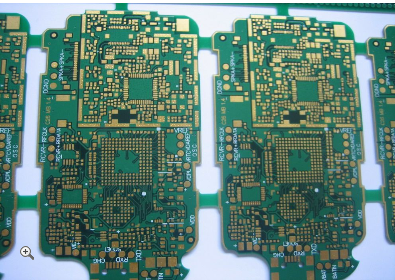

- PCB & PCBA

- Air Quality Appliances

- Home Appliance Parts

- Heating & Cooling Appliances

- Small Kitchen Appliances

- Laundry Appliances

- Water Heaters

- Water Treatment Appliances

- Refrigerators & Freezers

- Personal Care & Beauty Appliances

- Major Kitchen Appliances

- Cleaning Appliances

- Second-hand Appliances

- Smart Home Appliances

- Other Home Appliances

- Energy Chemicals

- Inorganic Chemicals

- Basic Organic Chemicals

- Agrochemicals

- Admixture & Additives

- Catalysts & Chemical Auxiliary Agents

- Pigments & Dyestuff

- Coating & Paint

- Daily Chemicals

- Polymer

- Organic Intermediate

- Adhesives & Sealants

- Chemical Waste

- Biological Chemical Products

- Surface Treatment Chemicals

- Painting & Coating

- Chemical Reagents

- Flavor & Fragrance

- Non-Explosive Demolition Agents

- Other Chemicals

- Custom Chemical Services

Key Principles Of EMI Reduction Through Careful Electronics Layout Design

In the intricate world of modern electronics, where devices operate at ever-increasing speeds and densities, a silent and invisible challenge persistently threatens performance and regulatory compliance: Electromagnetic Interference (EMI). EMI refers to the disruptive electromagnetic energy emitted from an electronic device that can interfere with the operation of other nearby devices or the device itself. As systems become more compact and functionalities more integrated, the potential for EMI grows exponentially, making its mitigation not merely an afterthought but a fundamental design imperative. While components selection and shielding are crucial, the first and most impactful line of defense lies in the careful, strategic design of the printed circuit board (PCB) layout itself. A well-architected layout can prevent noise generation and coupling at the source, often rendering costly corrective measures like additional shielding unnecessary. This article delves into the key principles of EMI reduction through meticulous electronics layout design, exploring foundational strategies that empower engineers to create robust, reliable, and compliant products from the ground up. By mastering these layout techniques, designers can tame electromagnetic emissions, ensuring their creations function flawlessly in our increasingly connected electromagnetic environment.

Strategic Component Placement and Partitioning

The battle against EMI begins with the strategic placement of components on the PCB. This initial step sets the stage for all subsequent routing and is critical for containing noise. The fundamental rule is to physically separate circuits based on their function and speed. The board should be partitioned into distinct areas: a clean, quiet zone for analog and sensitive circuits (like sensors or RF receivers), a controlled zone for digital processing, and a separate, well-contained zone for high-power or noisy circuits (such as switching regulators, motor drivers, or clock generators).

This partitioning prevents noise from high-speed digital or power sections from capacitively or inductively coupling into sensitive analog traces. Furthermore, components should be placed to minimize the length of critical high-speed traces. Clock generators, oscillators, and drivers should be positioned as close as possible to the devices they serve. By reducing the physical length of these potential antennas, the loop area for radiating electromagnetic energy is significantly minimized, directly reducing emitted interference.

Meticulous Power Distribution Network (PDN) Design

A robust and quiet Power Distribution Network is the cornerstone of a low-EMI design. The primary goal is to provide a stable, low-impedance power source to all ICs across a wide frequency range. A common failure is to treat power traces as simple connections, neglecting their behavior as transmission lines at high frequencies. The use of dedicated power and ground planes in a multilayer board is highly recommended. These planes create a natural distributed capacitance, offering a very low-impedance return path for high-frequency currents.

Decoupling capacitors are vital components of the PDN and must be placed with precision. Large bulk capacitors handle lower frequency demands, while smaller, low-inductance ceramic capacitors (e.g., 0.1µF, 0.01µF) must be placed as close as possible to the power pins of each IC. This proximity is non-negotiable; it minimizes the parasitic inductance of the connection, allowing the capacitor to effectively "short" high-frequency noise on the power rail to ground locally before it can propagate across the board. A multi-value decoupling strategy often works best to address a broad spectrum of noise frequencies.

Controlled Impedance Routing and Signal Integrity

For any high-speed signal—typically where the trace length approaches 1/10th of the signal's wavelength—controlled impedance routing becomes essential. Uncontrolled impedance leads to signal reflections, which manifest as ringing, overshoot, and increased EMI. Traces must be designed as transmission lines with a specific characteristic impedance (e.g., 50Ω, 75Ω) matched to the source and load. This is achieved by carefully calculating and controlling the trace width and its distance to an adjacent reference plane (ground or power).

Critical signals, especially clocks and high-speed data lines, should be routed on layers adjacent to a solid reference plane. This confines the electromagnetic fields between the trace and the plane, reducing both radiation and susceptibility. Furthermore, these traces must be kept short, straight, and avoid sharp 90-degree corners, which can cause impedance discontinuities. Using 45-degree angles or curved traces is preferable. Differential pair routing (for USB, Ethernet, etc.) must maintain consistent spacing (coupling) between the pair and equal length to preserve common-mode noise rejection.

Comprehensive Grounding Strategy

Perhaps no other topic in EMI control is as critical and misunderstood as grounding. A poor ground system is the single largest contributor to EMI problems. The key principle is to minimize ground impedance and avoid ground loops. For mixed-signal boards, the recommended approach is often a single, contiguous ground plane. While intuitively one might think to split analog and digital grounds, this can create more problems than it solves by forcing return currents to take long, inductive paths that increase radiation.

Instead, a unified ground plane provides the lowest impedance return path. Separation is achieved by partitioning the components on the board and carefully routing signals so that high-speed digital return currents do not flow under sensitive analog sections. For systems with very high-noise isolated sections (like a relay driver), a single-point "star" ground connection to the main ground plane may be used. The grounding scheme for cables and shields must also be considered; shield connections should be bonded to the chassis or ground plane at a single, clean point to prevent noise currents from flowing on the shield.

Shielding, Filtering, and Layout Finishing Touches

While a good layout minimizes the need for additional measures, shielding and filtering act as essential safeguards. Filtering involves placing passive components like ferrite beads, inductors, and capacitors at board interfaces (power entry, I/O connectors) to block conducted EMI from entering or leaving the board. These filter components must be placed right at the connector entry point, with their ground connections tied directly to a clean reference plane to be effective.

Finally, attention to layout details is paramount. Avoid leaving unused copper areas floating, as they can act as antennas; tie them to ground. Provide ample stitching vias when a return current must change reference planes, ensuring a continuous low-impedance path. For very sensitive designs, a grounded "guard ring" or trace around a critical circuit can help shunt away stray fields. By integrating these principles from the initial design phase, engineers create a layout that is inherently quiet, turning EMI reduction from a reactive troubleshooting exercise into a proactive design achievement.

REPORT